The Handling Scripture series of articles offers thoughts that spring off of the previous post about God, found here:

When one considers that Jesus is the clear, culminating, and even corrective revelation of who and what God is, how do we carry this into our reading of Scripture?

Particularly, how do we deal with the places in the First Testament that has God not looking at all like Jesus?

Peter struggled with this often, including on the Mount of Transfiguration (Matthew 17:1-8).

In telling the story of the transfiguration, Matthew demonstrates the contrast between Jesus and the First Testament. His entire gospel is a reframing of the First Testament with Jesus as the focal point of everything. And we see this play out in the transfiguration imagery between Jesus and the figures of Moses and Elijah.

Before the eyes of Peter (James and John as well, but Matthew makes Peter the focal point of the three), Jesus is suddenly transfigured so that he shines with a brilliant light. Then, “suddenly,” Peter sees Moses and Elijah appear, and they are talking to the shining Jesus.

Peter does not watch Moses and Elijah walk up to Jesus and begin speaking. Rather, in the lifting of a curtain for Peter to be able to discern Jesus as full of the divine light, it is as if a curtain is also lifted for Peter to discover an already begun conversation between Jesus (the Word) and Moses and Elijah.

Moses and Elijah were immediately understood by the early church to be the personification of the Law and the Prophets. In other words, they embodied on the mountain: the pre-Jesus Scriptures.

Peter is given a view of the pre-Jesus Scriptures (our First Testament) engaging with Jesus in a conversation. Peter did not observe Moses and Elijah approaching and initiating a conversation, because this conversation had been going on for thousands of years before being revealed to Peter.

Upon seeing this conversation, Peter gets excited and speaks out of turn - as he is prone to do. Peter attempts to do the same thing that much of the modern, western church does today. Peter seeks to place Jesus on equal footing with Moses and Elijah - the First Testament. He says that he will build three tabernacles - three places of honor - one for Jesus, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.

However, the deliberate word picture Matthew paints here is crucial to note. Out of three embodiments Peter is seeing - Jesus embodying God and Moses and Elijah embodying the First Testament - it is only Jesus who shines forth divine illumination.

Peter is mistaken in his plan of equal honor to place Jesus alongside the Law and the Prophets. His mistake is noted by many through Church history. Two of note include:

“You are astray Peter! [As Luke] testifies: You do not know what you are saying… by no means can you compare the servants with their Master.” - St. Jerome

“What do you say, O Peter? Did you not a little while since distinguish Him from the servants? Are you again numbering Him with the servants?” - St. John Chrysostom

These two church fathers, along with many others, note that Jesus is not equal to the “servants” - Moses and Elijah, and Peter is mistaken to think otherwise.

St. John Chrysostom’s words recall that Peter had just distinguished Jesus from Moses and Elijah, in Peter’s famous declaration of who Jesus is as the Son of God (Matthew 16:13-20), and Peter is making a mistake by now reducing Jesus as equal with them.

Peter’s over eager mistake is corrected as the lesson of the transfiguration culminates. The lesson continues as his plan of equality is interrupted while he is still talking. We read that while Peter was telling of his plan the cloud of God’s divine glory comes over them. The cloud causes Peter to lose sight of Moses and Elijah, as well as Jesus to whom he was talking. From the cloud, Peter hears God declare Jesus as the Son, the Beloved (one of a kind), the delight of God, and God declares: “Listen to him.”

After the declaration, the cloud leaves and Moses and Elijah are gone. Their conversation with Jesus has reached its completion, and they have been swallowed up and eclipsed by the Divine. Jesus is the sole, divinely declared, voice to which we listen and to which Jesus’ servants, submit.

The servants of the Law and the Prophets have no light, and do not illuminate. Rather, Jesus illuminates them. Jesus alone is light.

There is no enlightenment that can be claimed except light that originates from Jesus.

So, as we approach Scripture, we approach with Jesus as our defining factor.

This is often referred to as a Christocentric hermeneutic.

“Hermeneutic” is the fancy word for how we interpret what we are reading in our Scriptures.

“Christocentric” means that our interpretation is centered on Christ.

In other words, a Christocentric hermeneutic is to have our understanding of Scripture anchored in Christ.

Using the Mount of Transfiguration example, the Christocentric view considers Jesus to be the only divine light by which we are able to see at all the rest of Scriptures that do not contain their own light.

Taking from the image of the shining Jesus at the transfiguration, we might say in modern words that Jesus is our flashlight that we shine on otherwise dark Scripture, in order to see it clearly.

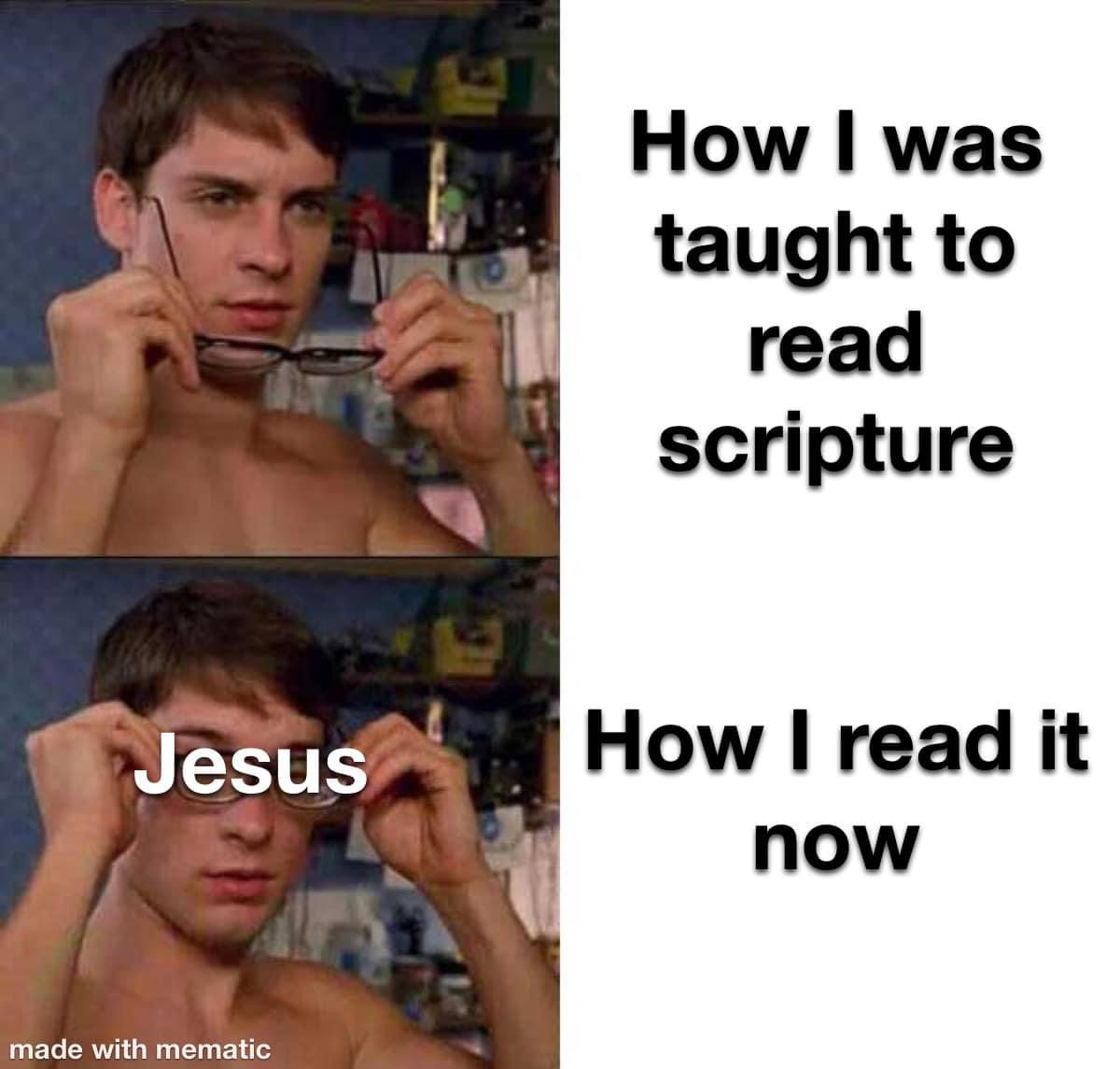

Another common way this is understood, is to consider Jesus to be the lenses through which we read Scripture. With our Jesus lenses, Scripture comes into focus and becomes understandable.

The problem with Christocentricity is that people still don’t agree on how to understand the life of Jesus, especially in relation to the First Testament.

Very often, the First Testament is considered illuminating in its own right. And it is held to provide its own enlightenment that is independent and much different from Jesus’ light. The Church then reads Jesus’ life based upon enlightenment of the First Testament. The servant is placed over the Master, or at least called another master, equal to the Master.

Another way to say this, is that Jesus’ revelation is made subservient to the First Testament. His declarations and actions are not allowed to stand in their own right, but are tempered and limited by reducing him to equality rather than authority with the Law and the Prophets. Moses and Elijah, the servants, are given authority over Jesus by being given equality with him.

With this problematic approach, Jesus is reduced from being the full and complete revelation of God, to being only a completing part of the revelation of God.

This approach is incorrect. But those who hold this view will often still claim to hold to a Christocentric hermeneutic, even though their center also lists Moses, Elijah, and the rest of the First Testament.

In order to avoid this error, it is necessary to properly define Christocentricity.

It is to the proper definition of Christocentricity that we turn to conclude part one of the series: Handling Scripture.

Leading up to the transfiguration, Jesus asks his disciples, “Who is Jesus? Who am I?”

Peter, ever the eager one, jumps in and declares, “You are the Christ!” (Matthew 16:16).

Jesus rejoices at Peter’s words, and now the disciples know who Jesus is. From that moment, Jesus begins to educate them on what that means Jesus is. The who of Jesus is that he is the Christ, and what Jesus is, as the Christ, is the God of Love, the co-sufferer with humanity who is to go to Jerusalem where he will suffer and die (Matthew 16:21).

In short, to be the Christ is to be the co-suffering God who will climb upon the cross of human suffering.

During Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness, Satan attempted to turn Jesus into a God who does not suffer. He first attempted to get Jesus to alleviate his own suffering of hunger. When that failed, Satan offered Jesus the chance to secure the world without the suffering of the cross.

Jesus refused to be Christ without a cross.

Or, it might better be said, that without a cross, one cannot be the Christ.

Then, as Peter hears what Jesus says it means to be the Christ, that Jesus must go to suffer and die with and for humanity, Peter pulls Jesus aside and refuses the plan. Peter wants a Christ who does not suffer. Peter wants Jesus to go down Satan’s route of non-suffering.

In his Satan-like endeavor to also make Jesus the Christ without a cross, Jesus calls Peter “Satan” (the word means adversary).

The lesson is: to separate the Christ from the crucifixion is satanic.

Many times, Jesus demonstrates that a God who suffers for us and with us, is also a God who suffers us.

This is all summed up on the cross.

This is Love.

What Love is, is often hotly contested, but God, enfleshed in Jesus, has defined Love - capitol-L Love.

John tells us this in 1 John 3:16: “This is how we know what love (agape) is, Jesus, the Christ, laid down his life for us.”

In the enlightened writings, now composed in the clarity of Jesus’ light, we read:

Jesus is the complete revelation of God exposed to human eyes (see last post; Hebrews 1:3)

God is Love (1 John 4:8)

Love is the Christ inseparable from the cross (Matthew 16:23; 1 John 3:16)

With this consideration, we come to understand that we cannot refer to Christ without the crucifixion - a crucifixion free Christ is satanic. The crucifixion is the single thing that defines the Christ, and upon which the rest of Jesus’ life and everything else is understood.

Thus, to speak of a ‘Christ’-ocentric reading of Scripture is to say that above all else, “Christ crucified” is held at the center of our understanding of all Scripture.

Christocentricity, properly understood, is to understand that its synonym is crucicentricity. A Christocentric reading of the Bible can only be a crucicentric reading of the Bible. In order to avoid misunderstandings with those who claim to handle Scripture Christocentrically, but are really Jesus-and…-centric (piling a bunch more in the middle than just Christ), true Christocentrism can also be referred to as crucicentrism.

God is Love, and what God is, is defined at the crucifixion, and it is through that lens - or with that flashlight - that we handle Scripture that has no illumination of its own.

Our understanding of God, our understanding of Love, our understanding of Christ, is to be cruciformed - that is formed, shaped, by the crucifixion.

Now that we understand, like Peter was shown, that we are to place the servants, the First Testament, under the authority of Jesus (God enfleshed), and that Jesus was defined by being the Christ, and that the Christ was defined at the crucifixion, we come to realize that we handle Scripture crucicentrically, we will dig deeper into how that works with the next article.

The next article will look at Scripture’s inerrancy and infallibility from a crucicentric hermeneutic.